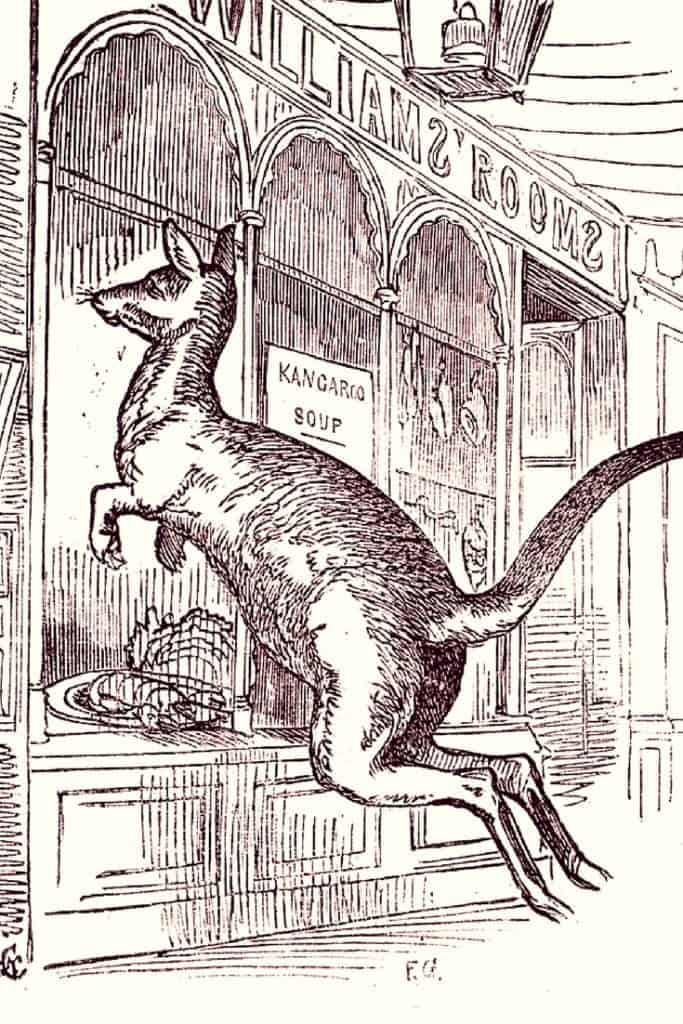

I confess that I saw this drawing “Jumping to a Conclusion” first. And having found the image I knew I had to write something to write about so I could use it. Like the creative writing exercises I used to do in primary (elementary) school. Only different.

Fortunately, the Productive Woman podcast came to the rescue with a recent episode called The Stories We Tell Ourselves.

Jumping to a Conclusion

In your daily life, you often make observations; for example, you see that the sun is out. Then you make inferences about them (as the sun is out, it is warm outside). Followed by predictions (I will be warm enough without a cardigan).

You can already guess that while your predictions are logically consistent, they are not always accurate. They might even be specious!

According to Mark Dombeck (site no longer exists), it’s a form of cognitive bias that comes in several forms:

- Mind Reading: when you think you know that other people’s thoughts and beliefs about you are negative.

- Labelling: when you apply wild generalisations because you believe they are true. For example, that someone who spends less on something than you is a miser.

- Blame: taking or allocating blame for everything; that you are responsible for the milk being sour because you looked at it.

- “Musterbation”: pretty much any statement that includes should, must, or ought. They generally aim at perfection and are impossible to meet.

Jumping to a Conclusion is Bad

We can infer from this that jumping to a conclusion is bad. That’s why it’s jumping – it goes along with “look before you leap.” There are myriads of ways it is bad, but here are just three of them.

1. You Aren’t at Your Best

Gwen Moran suggests that one of the most common reasons you jump to conclusions is that you just don’t have the available brainpower at that time. You are too tired or hungry to think properly. Or maybe the air in your meeting room is stale, or the colour scheme isn’t conducive.

2. You’re Ignoring All the Available Evidence

Jumping to a conclusion is almost always a gut-based reaction. According to Mike Myatt, you don’t stop to compare your knowledge and experience with the available data and information. Nor do you take into account the credibility of the source (you) on this issue.

3. You Aren’t Outcome Oriented

Jumping to a conclusion looks backwards not forwards. Z. Hereford (site since closed down) argues that you need to consider the possible outcomes. What are the best and worse case scenarios, what are the pros and cons? Is it possible that you are facing an opportunity?

How to Make Better Choices

By now you probably agree that you need a decent meal and a good night’s sleep, along with access to high-quality information and a future-oriented frame of mind when you make important choices like whether to:

- Marry the schmuck that turned up at the casino after you won big.

- Invest in that “too good to be true” time-share scheme.

- Buy the house held together by duct tape.

So to close the loop, here are three suggestions for drawing easy but better conclusions.

1. Take the Perspective of Someone Else

That might be Jesus or the Buddha, but it could just as easily be someone you know and trust. What would they do in this situation?

2. Start With the Right Question

According to Eric Barker, it’s not that you need a lot of information, it’s more that you need the right information for your specific problem.

3. Think About What’s Best For You

Often your choices reflect the thoughts and opinions of others, for example, you parents, colleagues or a celebrity you have been following (on social media, not skulking down the street after). Marcia Reynolds says that in the end, the obligations you place on yourself on behalf of those people are not as important as choosing the outcome that is best for you.

Resolution

In the long run, the conclusions you draw and the actions you take will always come from you. You can improve the conclusions you jump to by examining the adequacy of your assumptions and decisions on an ongoing basis. Going back to Eric Barker, start a decision diary detailing the decisions you make, what you expect, and the outcomes. You can include relevant information about your physical and mental state and the points you thought were particularly relevant. Look back when the outcome is clear to see what thought processes you might need to change. And if you are that way inclined, you could take the results and develop a checklist to guide you in future decisions.